What is old (prereform, prerevolutionary) orthography?

It is the Russian language orthography that people had used from the time of Peter the Great till the spelling reform of 1917-1918. It had been changing, of course, during the last 200 years and we will observe spelling from the end of XIX to the beginning of XX century period – the same state it was when the last reform had happened.

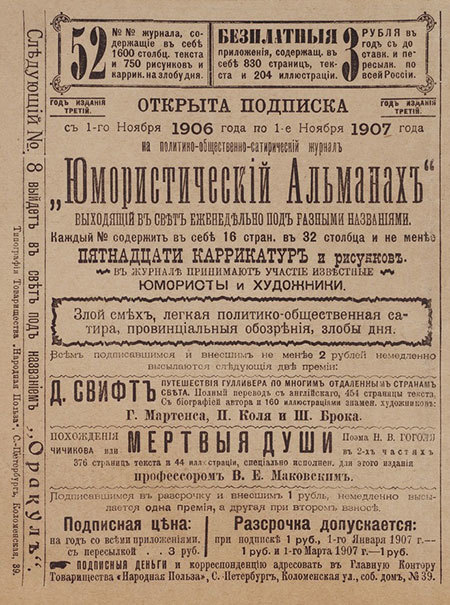

The advertisement page of humorous almanac “Podarok”, Saint Petersburg, 1906. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

What is the difference between old and modern orthography?

Before the 1917-1918s reform Russian alphabet contained more letters than it has now. Besides current 33 letters, it contained i (“i desyatirichnoe”, reads like Russian “и”), ѣ (yat, reads like Russian “е”, in italic looks like ѣ), ѳ (fita, reads like Russian “ф”) and ѵ (izhitsa, reads like Russian “и”). Moreover, the letter “ъ” (yer, i.e. hard sign) was used much more often. Most of the differences between the prereform orthography and the current one are related to the use of these letters, but there are a number of others. For example, the use of different endings in some cases and numbers.

How to use ъ (yer, hard sign)?

It is the simplest rule. In prereform orthography the hard sign (i.e. yer) is used at the end of any word that ends with consonant: столъ, телефонъ, Санктъ-Петербургъ. The same rule is for words with hushes at the end: мячъ, ужъ замужъ невтерпежъ. The exception is words ending with short Russian i: й was a vowel. In prereform orthography hard sign should be also used in such Russian words now ending with soft sign: олень, мышь, сидишь.

How to use i (“i desyatirichnoe”)?

This is simple too. It should be written instead of the current и if afterwards follows another vowel (including й by prereform rules): линія, другіе, пріѣхалъ, синій. The only word where the spelling of i doesn’t follow this rule is міръ meaning “earth, Universe”. Thus, in prereform spelling word миръ (the absent of war) had been opposed to the word міръ (Universe). Opposition disappeared when “i desyatirichnoe” had been cancelled.

How to use ѳ (fita)?

The letter “fita” was used in the limited list of Greek origin words (and this list was reduced over time) instead of the current ф – in those places where it was “theta” (θ) in Greek: Аѳины, акаѳистъ, Тимоѳей, Ѳома, риѳма etc. Here is the list of words with fita:

Proper names: Агаѳья, Анѳимъ, Аѳанасій, Аѳина, Варѳоломей, Голіаѳъ, Евѳимій, Марѳа, Матѳей, Меѳодій, Наѳанаилъ, Парѳенонъ, Пиѳагоръ, Руѳь, Саваоѳъ, Тимоѳей, Эсѳирь, Іудиѳь, Ѳаддей, Ѳекла, Ѳемида, Ѳемистоклъ, Ѳеодоръ (Ѳёдоръ, Ѳедя), Ѳеодосій (Ѳедосій), Ѳеодосія, Ѳеодотъ (Ѳедотъ), Ѳеофанъ (но Фофанъ), Ѳеофилъ, Ѳерапонтъ, Ѳома, Ѳоминична.

Geographical names: Аѳины, Аѳонъ, Виѳанія, Виѳезда, Виѳинія, Виѳлеемъ, Виѳсаида, Геѳсиманія, Голгоѳа, Карѳагенъ, Коринѳъ, Мараѳонъ, Парѳія, Парѳенонъ, Эѳіопія, Ѳаворъ, Ѳеодосія, Ѳермофилы, Ѳессалія, Ѳессалоники, Ѳивы, Ѳракія.

Nations (and citizens): коринѳяне, парѳяне, скиѳы, эѳіопы, ѳиване.

Common names: анаѳема, акаѳистъ, апоѳеозъ, апоѳегма, ариѳметика, диѳирамбъ, еѳимоны, каѳолическій (yet католическій), каѳедра, каѳизма, киѳара, левіаѳанъ, логариѳмъ, мараѳонъ, миѳъ, миѳологія, моноѳелитство, орѳографія, орѳоэпія, паѳосъ (passion, yet Пафосъ — island), риѳма, эѳиръ, ѳиміамъ, ѳита.

When to white ѵ (izhitsa)?

Almost never. Izhitsa remained only in the word мѵро (миро – Holy oil) and in some other church terms: ѵподіаконъ, ѵпостась etc. This letter has also a Greek origin and corresponds to the Greek letter “ypsilon”.

What should you know about the endings?

Adjectives in the masculine and neuter genders that in the nominative singular have the endings -ый, -ій, in the genitive end with -аго, -яго.

«А бобренокъ сидитъ, глаза на всѣхъ таращитъ. Не понимаетъ ничего. Дядя Ѳедоръ ему молока далъ кипяченаго» («Дядя Ѳедоръ, песъ и котъ», “Uncle Fedya, His Dog, and His Cat”).

«Вотъ онъ [шарикъ] пролетѣлъ послѣдній этажъ большущаго дома, и кто-то высунулся изъ окна и махалъ ему вслѣдъ, а онъ еще выше и немножко вбокъ, выше антеннъ и голубей, и сталъ совсѣмъ маленькій…» («Денискины разсказы», “The Adventures of Dennis”).

Adjectives in the feminine singular and neuter singular genders end with -ыя, -ія (not with -ые, -ие, as they do now). The third person pronoun of the feminine gender она in the genitive case has the form ея, in contrast to the accusative form её (now её is used everywhere).

«Ну и что? — говоритъ Шарикъ. — Необязательно большую корову покупать. Ты купи маленькую. Есть такія спеціальныя коровы для котовъ. Козы называются» («Дядя Ѳедоръ, песъ и котъ», “Uncle Fedya, His Dog, and His Cat”).

«А деньги я вамъ высылаю — сто рублей. Если у васъ останутся лишнія, пришлите обратно» («Дядя Ѳедоръ, песъ и котъ», “Uncle Fedya, His Dog, and His Cat”).

«Въ то время у мамы былъ отпускъ, и мы гостили у ея родныхъ, въ одномъ большомъ колхозѣ» («Денискины разсказы», “The Adventures of Dennis”).

What should you know about the prefixes?

In the prefixes ending with consonant з (из-, воз-, раз-), it is preserved before the following с: разсказъ, возсіялъ, изсякъ. In the prefixes без- and чрез-/через- the final з is always preserved: безполезный, черезчуръ.

The hardest thing: how to write yat?

The rules of using the letter yat unfortunately cannot be described that simple. It is the yat that created a lot of problems for prerevolutionary high-school students who had to learn long lists of words with this letter (almost the same way modern students learn “dictionary words”). There is a renown mnemonic poem «Бѣлый бѣдный блѣдный бѣсъ» (“Poor White Pale Devil”), although it was not the one of a kind. The thing is that spelling with yat mainly followed the etymological rule: during the earlier period of Russian language history, the letter “yat” corresponded particular sound (middle between [и] and [э]) which later in pronunciation merged with the sound [э]. The difference in spelling, however, had been remaining for several centuries until yat was replaced everywhere with the letter «е» (with some exceptions discussed below) during the reform of 1917-1918 years.

Бѣлый, блѣдный, бѣдный бѣсъ

Убѣжалъ голодный въ лѣсъ.

Лѣшимъ по лѣсу онъ бѣгалъ,

Рѣдькой съ хрѣномъ пообѣдалъ

И за горькій тотъ обѣдъ

Далъ обѣтъ надѣлать бѣдъ.

Вѣдай, братъ, что клѣть и клѣтка,

Рѣшето, рѣшетка, сѣтка,

Вѣжа и желѣзо съ ять —

Такъ и надобно писать.

Наши вѣки и рѣсницы

Защищаютъ глазъ зѣницы,

Вѣки жмуритъ цѣлый вѣкъ

Ночью каждый человѣкъ…

Вѣтеръ вѣтки поломалъ,

Нѣмецъ вѣники связалъ,

Свѣсилъ вѣрно при промѣнѣ,

За двѣ гривны продалъ въ Вѣнѣ.

Днѣпръ и Днѣстръ, какъ всѣмъ извѣстно,

Двѣ рѣки въ сосѣдствѣ тѣсномъ,

Дѣлитъ области ихъ Бугъ,

Рѣжетъ съ сѣвера на югъ.

Кто тамъ гнѣвно свирѣпѣетъ?

Крѣпко сѣтовать такъ смѣетъ?

Надо мирно споръ рѣшить

И другъ друга убѣдить…

Птичьи гнѣзда грѣхъ зорить,

Грѣхъ напрасно хлѣбъ сорить,

Надъ калѣкой грѣхъ смѣяться,

Надъ увѣчнымъ издѣваться…

What should the modern prereform orthography lover do if he or she wants to penetrate all the spelling nuances of yat? Should the person follow the lead of the Russian Empire high-school students and learn poems about the poor devil? Fortunately, every cloud has a silver lining. There are a number of patterns that collectively cover a significant part of cases of writing yat – thus, following these patterns will help avoiding the most common mistakes. Let’s consider these patterns in more details: first, we will review the cases where yat cannot be written then the ones where it should be.

Firstly, yat is not spelled in the place of е which alternates with zero sound (missing of vowel): левъ (не *лѣвъ), ср. льва; ясенъ (не *ясѣнъ), ср. ясный etc.

Secondly, yat is not spelled in the place of е which now alternates with ё and in the place of the ё itself: весна (не *вѣсна), ср. вёсны; медовый, ср. мёдъ; исключения: звѣзда (ср. звёзды), гнѣздо (ср. гнёзда) and some other.

Thirdly, yat is not spelled in pleophonic combinations -ере-, -еле- and in nonpleophonic combinations -ре- and -ле- between consonants: дерево, берегъ, пелена, время, древо, привлечь (exception: плѣнъ). Furthermore, as a rule, yat is not spelled in combination -ер- ahead of consonant: верхъ, первый, держать etc.

Fourthly, yat is not spelled in words roots that have obvious foreign (non-Slavic) origin including proper names: газета, телефонъ, анекдотъ, адресъ, Меѳодій etc.

As for spelling where yat should be, there are two main rules.

First, the most common rule: if е in the word is written now ahead of hard consonant and does not alternate with zero sound or ё, it is very likely in prereform orthography in the place of that е the yat should be written. Examples: тѣло, орѣхъ, рѣдкій, пѣна, мѣсто, лѣсъ, мѣдный, дѣло, ѣхать, ѣда and many other. It is important to consider the mentioned limitations including pleophony, nonpleophony, loanwords and so on.

Second rule: yat is written on the place of current е in most of the grammatical morphemes:

in the case endings of the indirect cases of nouns and pronouns: на столѣ, къ сестрѣ, въ рукѣ, мнѣ, тебѣ, себѣ, чѣмъ, съ кѣмъ, всѣ, всѣми, всѣхъ (indirect cases – all cases, except for the nominative and accusative, in these two cases the yat is not written: утонулъ въ морѣ — prepositional, поѣхали на море — accusative);

in the suffixes of superlative and comparative adjectives and adverbs -ѣе (-ѣй) and -ѣйш-: быстрѣе, сильнѣе, быстрѣйшій, сильнѣйшій;

in the stem-forming suffix of verbs ending with -ѣть and deverbal nouns: имѣть, сидѣть, смотрѣть, имѣлъ, сидѣлъ, смотрѣлъ, имѣніе, покраснѣніе etc. (nouns ending with –еніе formed from other verbs should be written with е: сомненіе — cf. сомневаться; чтеніе — cf. читать);

in the end of most prepositions and adverbs: вмѣстѣ, кромѣ, возлѣ, послѣ, налегкѣ, вездѣ, гдѣ, внѣ;

in the prefix нѣ- with the meaning of uncertainty: нѣкто, нѣчто, нѣкий, нѣкоторый, нѣсколько, нѣкогда (когда-то). In this case, a negative prefix and the particle are written with «е»: негдѣ, не за что, не съ кѣмъ, некогда (нет времени).

Finally, there are two cases where yat in the ending should be written in a place of the current и: онѣ and однѣ – «они» and «одни» towards feminine nouns, as for однѣ – in the indirect cases as well: однѣхъ, однѣмъ, однѣми.

«Ну что же. Пусть будетъ пуделемъ. Комнатныя собаки тоже нужны, хоть онѣ и безполезныя» («Дядя Ѳедоръ, песъ и котъ», “ Uncle Fedya, His Dog, and His Cat”).

«Посмотри, что твой Шарикъ намъ устраиваетъ. Придется теперь новый столъ покупать. Хорошо еще, что я со стола всю посуду убралъ. Остались бы мы безъ тарелокъ! Съ однѣми вилками («Дядя Ѳедоръ, песъ и котъ», “Uncle Fedya, His Dog, and His Cat”).

Moreover, knowing other Slavic languages may help in this challenging battle with the rules of using yat. Thus, very often in the place of yat in correspond Polish word will be written ia (wiatr — вѣтеръ, miasto — мѣсто), in Ukranian –i (діло — дѣло, місто — мѣсто).

As we mentioned earlier, following these rules will prevent mistakes in most cases. However, considering many nuances, exceptions, and exceptions from exceptions, it never hurts to check spelling in the dictionary, if you have doubts.