The History of the Russian Language: from Cyril and Methodius to the Present Day

What is the difference between Old Slavonic, Church Slavonic, and Old Russian languages? How and why did the dialects of the Russian language disappear? How did Pushkin manage to reconcile archaists and innovators? The answers to these questions are in our brief history of the Russian language.

The Invention of Writing and Diglossia Phenomenon

The history of the Russian literary language traditionally begins from the invention of writing. The first reliable written monuments appeared after the Christianization of Rus in 988. Some liturgical books translated from Greek into Slavic languages were brought to Russia from Bulgaria. These texts were written in Old Slavonic, an artificial written language created by Cyril and Methodius and their students.

When Old Slavonic texts appeared in Russia, their language was exposed to local East Slavic dialects by Russian scribes. As a result, the Russian version of the Old Slavonic arose, i.e., the Church Slavonic.

Simultaneously, Cyrillic writing was also used in the non-church sphere: trade, craft, and everyday practice. As writing in Russia became spreading, a specific linguistic situation appeared. Linguists call it diglossia. It is the combination of two languages functioning in a society where they do not coincide in their functions but complement each other. For Ancient Rus, Church Slavonic was the cultural language, the language of the church, and the official chronicle language. The language of customary law and everyday communication was the Old Russian language.

The Language of the Russian Folks

After the destruction of Kiev by the Tatars, the power center moved to the northeast. In 1326, Metropolitan Peter selected Moscow as his residence, and the Moscow dialect became the basis of the literary language. During this period, the historical conditions developed for the emergence of three nationalities: Russian (Great Russian), Ukrainian, and Belarusian. An independent history of the literary languages of these folks began.

An extensive administrative management system required as a centralized state began forming, so formal writing was actively developing. Clerks and their assistants worked in the prince’s chancelleries. The language of formal writing took its own form, terminology, and genres. Printing played an essential role in the normalizing activity and the promotion of the Moscow dialect. The printing house workers collated, edited, and proofread texts.

The Russian language of that period began to rely not on Church Slavonic tradition but on living processes. The Russian language democratization process should be viewed as two-way. Book Slavic language expanded its powers and modified into the so-called ”academic” type of literary language. On the other hand, formal texts based on colloquial speech and command language took the status of literary texts.

From Peter to Pushkin

Peter’s era was a time of reforms in all spheres, including language.

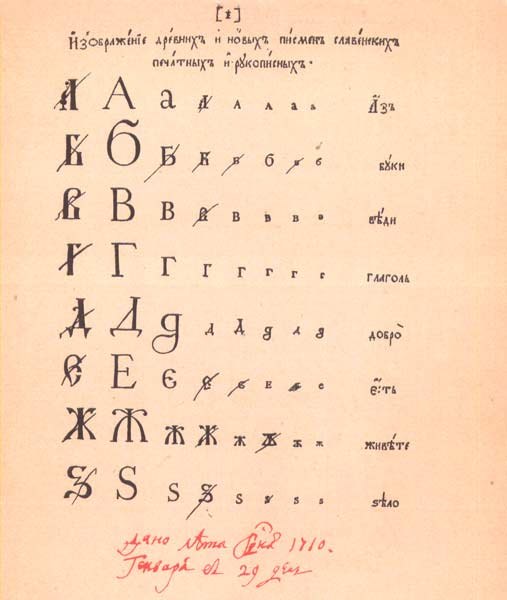

On the first edition of the Azbuka issued on January 29, 1710, it is written by Peter’s hand: “Сими литеры печатать исторические и манифактурныя книги. А которыя подчернены, тех вышеписанных книгах не употреблять” (literally, ”These letters to be used in historical and manufacturing books, and crossed out letters not to be used in the above books”).

Graphic reform was essential. In 1710, an alphabet was reformed: the so-called civil font was involved instead of the Cyrillic one. Creating a secular alphabet meant a sharp demarcation of secular literature from church theological literature. Some Greek letters were removed, and the Arabic numeral system was introduced.

This era is characterized by intensive enrichment of the language vocabulary. It is significant that the first dictionary of foreign words, “Lexicon to new vocabulary in alphabetical order”, was created during the reign of Peter I. Explanations were given in the form of Russian-language synonyms (“архитектор”, architect — “домостроитель”, housebuilder) or short explanations.

The tendency to exclude Church slavonicisms from the literary language that emerged in Peter’s era met a resolute rebuff from Mikhail Lomonosov who developed the theory of three styles. According to Lomonosov, style consists of an organized system of speech tools for which a range of fiction genres is assigned. The system of three styles is based on “the existence of three kinds of speech: the common Slavic vocabulary (бог, слава, рука), book vocabulary (отверзаю, господень), and primordial Russian words (пока, лишь, говорю).”

The system of three styles generally existed until the end of the 18th century. Mikhail Lomonosov developed his theory when high poetic genres and tragedy were the leading genres. In the second half of the 18th century, prose started to play a more significant role. The prose is heterogeneous: it could mix different styles depending on the topic. So, stylistic tools were gradually freeing from genre fixation.

At the end of the 18th century, it became necessary for Russian sentimentalism to use words enriched lexically and systematically, words that could more accurately describe feelings and analyze them. Nikolai Karamzin solved this problem. He introduced a lot of words borrowed from French into Russian. Alexander Shishkov became an ardent opponent of innovations. He was a fervent patriot and conservator who advocated high style.

So, two opposing groups were formed. Supporters of Karamzin, like writers and poets Zhukovsky, Pushkin, Batyushkov, and others, united in the Arzamas literary society. Conservatives and supporters of high style concentrated in the “Conversation of the Russian word lovers” community led by Shishkov.

Alexander Pushkin reconciled these two linguistic forces.

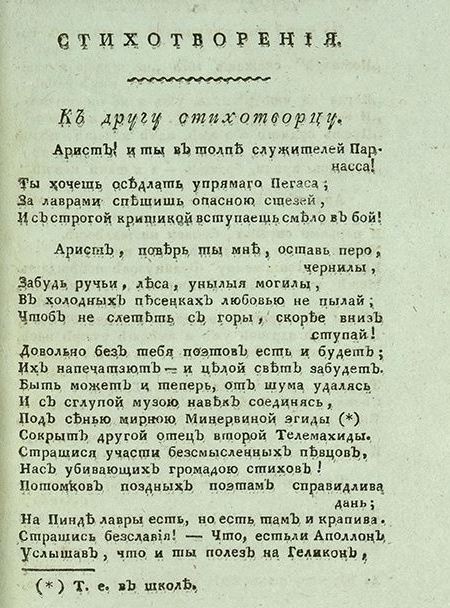

The first printed poem by A.S. Pushkin (“Vestnik Evropy” magazine, 1814, No. 13).

Pushkin strove to create a democratic national literary language based on the synthesis of the book language with live Russian speech and folklore poetry forms. He produced a synthesis of different sociolinguistic elements that historically formed the system of the Russian literary language: Church Slavicisms, Europeanisms (especially Gallicisms), and elements of live Russian speech.

The language of Pushkin’s works became the basis of the literary language that we speak today. This period in language history is often called “from Pushkin to the present day.”

Through the Crucibles of the 20th Century

Although the Russian literary language formation took place in the late 17th — early 19th centuries, the literary language also underwent some changes during the 20th century. These changes concern vocabulary and stylistics primarily.

The first years of the revolution are characterized by a spelling reform. In addition, a large number of words and expressions associated with the old state system and bourgeois life were eliminated from the active stock of literary vocabulary and phraseology.

After the October Revolution, new literary language speakers could not master the norms of the literary language in a short time. On the contrary, they brought their speech practice experience into various spheres of the literary language (newspapers, magazines, and texts of fiction), which resulted in the use of different-style linguistic elements in these sources.

With the further development of Soviet society, the industrialization of the country, and the collectivization of agriculture, a large number of new words and expressions enriched the language vocabulary. Some of them were previously known in the literary language but were not widespread, and some were created in the Soviet era. Women’s equality and the opportunity to work in a production triggered the emergence of newly formed nouns denoting female persons. Among the new words that became widespread in the Soviet era, portmanteau and abbreviations played an important role.

Significant changes also took place in the social functions of language. Literary language became the property of the broadest popular masses due to a number of reasons: the Cultural Revolution, the public education development, the distribution of books, newspapers, and magazines, radio, as well as the elimination of the former economic and cultural disunity of individual territories and regions. In connection with this, the process of loss of dialectal differences became more intense. Moreover, the Russian language turned into a tool of interethnic and international communication.